When drinking whiskey at a bar, most bartenders place the whiskey bottle in front of you. This is because reading the label while sipping is another interesting way to enjoy whiskey, beyond just drinking it.

Of course, those new to whiskey or still unfamiliar with it might find reading labels confusing. However, unlike wine labels written in French or Italian, whiskey labels originating from Scotland are all in English, making them much easier to understand. Moreover, whiskey labels are much simpler compared to wine labels.

Still, since many people find them unfamiliar, I want to provide a simple terminology guide for those looking to purchase whiskey or learn more about it. One advantage of whiskey is that due to its perception as a premium spirit, many people don’t know the terminology. In other words, knowing just a little can make you appear like an expert.

Key Terms on Whiskey Labels

Let’s look at important terms commonly found on whiskey labels. Reading English isn’t the problem – you just don’t understand what these terms mean. These terms help you understand whiskey’s characteristics and quality, and they’re useful when talking about whiskey. Actually, just knowing these is enough to fake being a whiskey expert. Let’s look at each key term.

Single Barrel or Single Cask

‘Single Barrel’ or ‘Single Cask’ means the whiskey came from just one barrel (cask). There’s no difference between barrel and cask – Americans use “barrel” while Scots use “cask.” Usually, they use 53-gallon (about 200-liter) white oak barrels, but there’s no size restriction.

Single barrel whiskeys are characterized by taste and aroma differences between each barrel. Even with the same ingredients and aging environment, since they don’t use exactly the same wood, wouldn’t the taste naturally be somewhat different? Single barrels are popular because even the same brand can have subtle taste differences. It’s interesting to taste them keeping this in mind, as the flavors do vary slightly.

Single Malt Whisky

‘Single Malt’ means malt whiskey made at one distillery. According to EU regulations, single malt must be distilled in pot stills and use barley as grain. In Scotland or Ireland, it must be aged at least 3 years to legally be called whiskey.

One common misconception about single malt is that it doesn’t necessarily mean using whiskey from just one barrel (cask). If it’s from one barrel, they more commonly use the term single barrel (or single cask). You can use the term single malt even when blending whiskey from multiple barrels and different years – the key is that it’s all produced at the same distillery. Single malt whiskey is currently the most popular because it best represents each distillery’s characteristics.

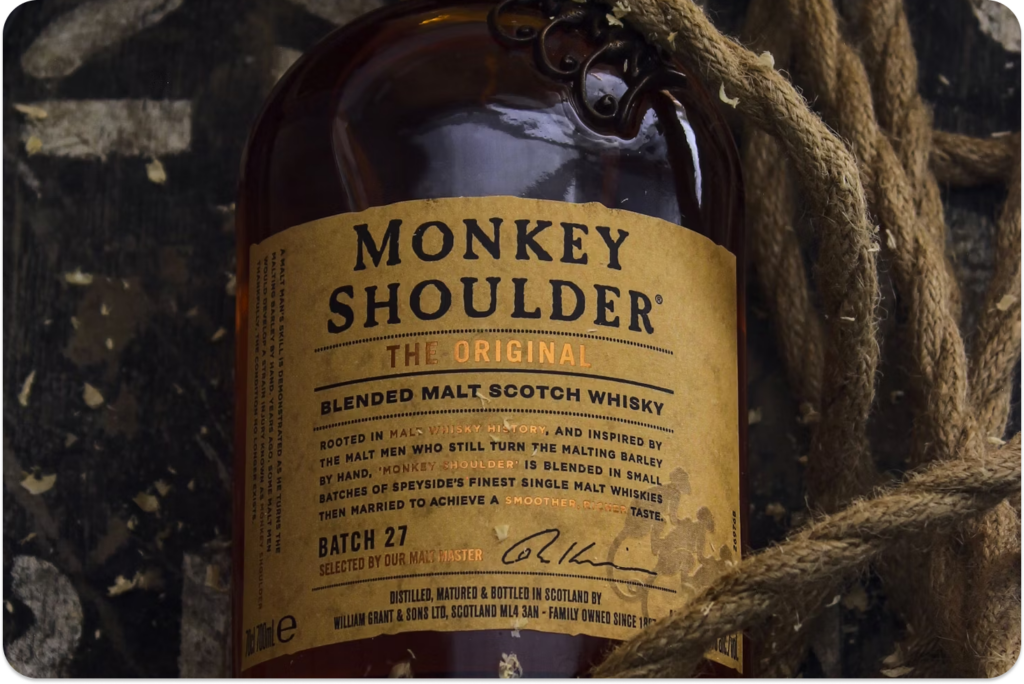

Blended Whisky

Blended whisky is divided into regular blended and blended malt.

Regular blended: Mixing malt and grain Blended malt: Mixing only single malts from different distilleries

This term, formerly called ‘Vatted Malt,’ means blending single malt whiskeys from two or more distilleries. You might find “vatted malt” on older bottles (which would probably be expensive, haha). Blended malt’s characteristic is its very consistent and smooth taste. Looking at blended whiskey’s history, it started when distilleries began mixing whiskeys from different distilleries to create a more appealing taste when single malts weren’t popular due to their strong personalities.

Personally, I think blended malts are more sophisticated and delicious than single malts because they require the skill to create harmonious flavors while maintaining each distillery’s characteristics. However, current trends favor single malts over blended. As trends come and go, the same applies to the whiskey industry. Well-known brands like Ballantine’s and Johnnie Walker are blended whiskeys.

Cask Strength

If you see ‘Cask Strength,’ it means the whiskey was bottled directly from the cask without adding water. Most Scotch whiskeys are uniformly 40% because water is added to achieve this percentage. While some say 40% is the most delicious alcohol content, it’s more accurate to say it’s done for productivity since whiskey must legally be over 40%. Cask strength typically has higher alcohol content (usually above 46%) because no water is added, and it’s popular among enthusiasts who want to enjoy the intense, rich original taste. Naturally, it’s also more expensive than regular whiskey.

The same concept is sometimes called “Barrel Strength” (in America), and Taiwan’s Kavalan uses the term “Solist.”

NCF (Non-Chill Filtered)

Chill filtering is an industrial process used to make whiskey appear clear. However, since this process can remove components that create taste and texture, many use ‘NCF’ or ‘non-chill filtered’ as a marketing term to indicate they’ve maintained the natural taste. You can taste a richer flavor in NCF whiskeys. Many brands have NCF product lines, including Ardbeg, Arran, and GlenAllachie, among others.

Age Statement

This isn’t complicated. If it says 12 years, it means the whiskey contains whiskey aged at least that long. As noted by “at least,” even if it says 12 years, it might contain whiskey aged longer. Recently, many NAS (No Age Statement) whiskeys are being released, so don’t think it’s strange if there’s no age statement, and higher age doesn’t automatically mean better whiskey.

Straight

This term is only used for American whiskeys. If you see this term, it’s likely bourbon or rye whiskey. ‘Straight’ whiskey means it’s been aged for at least 2 years in new oak barrels. However, straight corn whiskey can be aged in either used or new charred oak barrels. Different types of straight whiskey (e.g., bourbon, rye, wheat, corn) can be blended, but they must all be produced in the same state.

Bonded or Bottled-in-Bond

This term is also unique to American whiskey. ‘Bonded’ whiskey must meet strict criteria according to the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897. This law was originally created to guarantee whiskey quality and protect consumers.

Conditions for ‘bonded’ whiskey include:

- Must be made by one distiller at one distillery

- Must be produced during one distillation season (January-June/July)

- Must be aged at least 4 years in federally supervised bonded warehouses

- Must be bottled at exactly 50% ABV (100 proof)

- Cannot contain any additives except water

Due to these strict standards, ‘bonded’ whiskey is said to guarantee high quality and authenticity (though not always…). These conditions also make it relatively rare compared to regular whiskey.

Finish

Finish refers to additional aging in a different type of cask after initial maturation. This process can add new flavors and complexity to the whiskey. Usually, casks that held wine or fortified wine are used, with sherry finish being the most common. Other finishes include port, madeira, rum, and bourbon.

For example, if it says ‘sherry finish,’ it means the whiskey was first aged in regular oak barrels, then finished in casks that held sherry wine. This gives the whiskey characteristics of sherry wine’s sweet and fruity notes.

Finishing periods vary from months to years. Labels with terms like ‘Finish,’ ‘Double Wood,’ or ‘Triple Wood’ indicate this additional aging process.

Finishing is popular among whiskey enthusiasts as a way to give whiskey unique characteristics, as products from the same distillery can taste completely different depending on the finish. Glenfiddich 15 Year Solera Reserve, Balvenie DoubleWood, and Laphroaig PX Cask are all good examples of finishing.

Terms with Little or No Meaning

In the whiskey world, there are terms frequently used that don’t carry much actual significance. These terms are mainly used for marketing purposes and often lack legal definitions or are ambiguous. While good to know, they shouldn’t be major criteria when choosing whiskey. Let’s look at two prime examples:

Small Batch

‘Small batch’ is used to create an impression of limited production and exclusivity. However, there’s no legal standard for what constitutes “small.” Someone might claim it’s small batch because they used only 2-3 barrels, while large distilleries might consider 2,000 barrels relatively small when they produce tens of thousands annually. Ultimately, ‘small batch’ is just a relative concept defined arbitrarily by each brand.

Craft and Handmade, etc.

These terms are used to give the impression that the whiskey was carefully made with artisanal spirit. However, almost all whiskeys involve some degree of ‘handwork,’ making these terms ambiguous. Most whiskey production uses both automated equipment and manual processes. With no legal restrictions, even mass-produced products from large distilleries can use these expressions. Think about it – would there really be any whiskey made 100% by hand?

Other Considerations

Vintage Year and Bottling Year

Whiskey bottles often display years, and it’s important to carefully note whether it’s the vintage year (distillation year) or bottling year. Some whiskeys show both, so check whether it says “Bottled in” or “Matured in” around the year.

State of Distillation

All spirits must show their country of origin on the label. In the US, if the company address state differs from the actual distillation state, the distillation state must be shown.

How to Use Whiskey Terms

Now that you know the main terms appearing on whiskey labels and their meanings, let’s see how to use them when ordering at bars or buying at stores.

If All Whiskey Tastes the Same to You

At this level, it’s better to stick with basic whiskeys rather than anything too complex. For example, choose blended whiskeys or single malts with age statements.

If You’re Starting to Appreciate Flavors and Want Unique Experiences

At this level, try single barrel or cask strength whiskeys for more distinctive tastes. These typically offer more pronounced and intense flavors. Also, choosing whiskeys with NCF (non-chill filtered) markings might let you experience richer flavors than basic whiskeys.

If You Want Good Value for Money

If looking for good value whiskeys, choosing American whiskeys marked ‘bonded’ or ‘bottled-in-bond’ can be a good strategy. These whiskeys tend to guarantee quality due to strict government regulations. (Though again, not always..)

If You Want to Experience Richer Flavors Than Regular Whiskey

Try whiskeys with special finishes. Sherry finish is particularly popular because it imparts complex, rich fruit notes to the whiskey. Other finishes are good too. If it’s a Scotch whiskey finished in bourbon casks, it will have some of bourbon’s sweetness.

Finally…

When learning whiskey label terms, it’s easy to fall into certain prejudices: “NAS must be cheap because older whiskey is always better,” “single malt is the best,” “don’t drink anything without NCF,” “only stick to single cask,” etc. These thoughts might come naturally and often align with whiskey industry marketing strategies.

However, thinking carefully reveals how dangerous these prejudices can be. There are many excellent NAS whiskeys, and many masterpieces among blended whiskeys. Non-NCF whiskeys can be plenty delicious, and whiskeys blended from multiple casks might offer more complex and interesting flavors.

The most important thing is finding your own taste. Label information is just a guideline, not absolute criteria. Some people love peated Islay whiskeys, while others prefer smooth Highland whiskeys. Even the same person’s preferences might vary depending on mood and situation.

There’s no right or wrong way to drink whiskey. It’s just a process of finding what you like. Some days you might crave expensive whiskey, other days something cheaper but familiar. All these are valid ways to enjoy whiskey. The world of whiskey is truly endless. So don’t get too hung up on labels – enjoy it in various ways. After all, there are no rules for enjoying whiskey.